A little while ago, I wrote a post about compiling a master list of must-read authors. You can read that post here. It also made me wonder whether I should not create a new blog series, not unlike Art of Fantasy, except this one would focus on authors of past renown, whose works are now out of print and who had laid down the foundational pillars for genre fiction. These authors would come from the aforesaid list.

Today is the first entry of this new series.

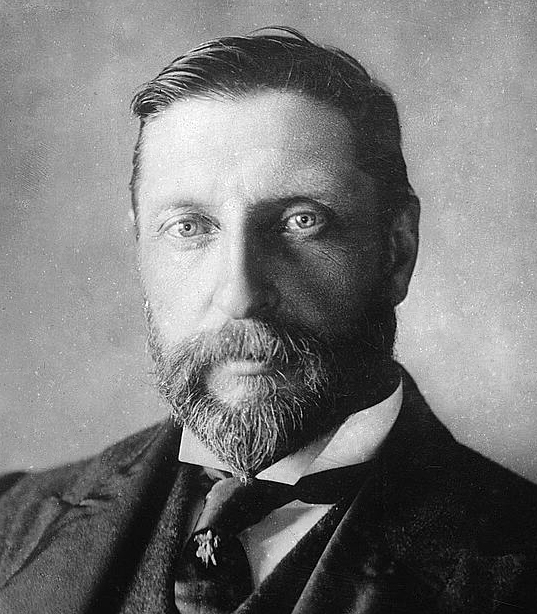

Rider Haggard: The Mythopoeic Gift That Never Stopped Giving

H. Rider Haggard wrote many books of adventure and action that broke the mould for how people would consume popular fiction in the future, to the chagrin of his many detractors who hissed and swiped at him like tomcats fighting over a female cat in heat. They probably made the same loud, piercing wail of impotent rage at being ousted by what they considered juvenile nonsense.

I wish more people knew about Ryder Haggard’s stories or the man himself. The barrister who longed to disappear into the exotic worlds of his heroes. Many know the epic tale of King Solomon’s Mines but not so many the name of its author. And that, dear reader, is a sad state of affairs, especially if you consider how Rider Haggard’s Lost World genre influenced so many popular novelists and pulp writers like Edgar Rice Burroughs, Robert E. Howard, Talbot Mundy, Philip José Farmer, Abraham Merritt, Rudyard Kipling, Arthur Conan Doyle, Sax Rohmer, Harold Lamb, H.P. Lovecraft, and Clark Ashton Smith.

Sir Henry Rider Haggard, more commonly known as Rider Haggard, was born in Norfolk, England on 22 June 1856 to wealthy landowners with both Jewish and Indian ancestry. Haggard is considered a Victorian writer of African frontier adventure novels, historical fiction, and to some extent, supernatural fantasy. His most well-known hero, the sharpshooting Allan Quatermain, made his first appearance with the novel King Solomon’s Mines, published in 1885. In the story, Allan Quatermain leads a group of Englishmen in search of the legendary diamond mines of King Solomon. But to get there they have to survive the harsh elements and dangers of savage Africa. Allan Quatermain would appear in 17 more novels covering decades of his adventurous life.

Allan Quatermain served as inspiration for the movie character Indiana Jones while Quatermain, in return, was inspired by the real-life escapades of Frederick Selous, a British big-game hunter and explorer of Colonial Africa. Haggard was also heavily influenced by the larger-than-life adventures of American Scout Frederick Russell Burnham.

Remember the movie The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen? Sean Connery played Allan Quatermain in that movie. Hallmark also released a TV Mini-Series based on the book in 2004, which starred the fantastic Patrick Swayze. And let’s not forget the two movies in the 80s, featuring Richard Chamberlain and Sharon Stone. Three other movies were made prior to these, in 1937, 1950, and 1979 respectively, but I have not seen them.

It is widely held that Haggard originated the Lost World literary genre but it’s probably more accurate to say he only popularised it. King Solomon’s Mines shaped and influenced future tales featuring the lost world narrative, of which authors so influenced include Rudyard Kipling’s The Man Who Would Be King (1888), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World (1912), A. Merritt’s The Moon Pool (1918), H. P. Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness (1931), and Edgar Rice Burroughs’ The Land That Time Forgot (1918) as well as The Return of Tarzan (1913) featuring the lost city of Opar, which, although influenced by King Solomon’s Mines, is purportedly based on the same Biblical Ophir King Solomon traded with.

However, before Alan Quatermain and before King Solomon’s Mines, others took the journey into the realm of lost and ancient worlds, such as Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s The Coming Race (1871) and Samuel Butler’s Erewhon (1872). And even before them, Simon Tyssot de Patot’s Voyages et Aventures de Jacques Massé (1710), explored prehistoric fauna and flora, and in Robert Paltock’s The Life and Adventures of Peter Wilkins (1751), the titular character undertakes an imaginary voyage during which he discovers a race of winged people on an isolated island surrounded by high cliffs, not unlike Burroughs’ Caspak.

The 1820 Hollow Earth novel Symzonia by Adam Seaborn has also been cited as the first of the lost world tropes, and Jules Verne’s Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864) and The Village in the Treetops (1901) further popularized the theme of hidden prehistoric species existing in isolated pockets on and inside the earth.

Haggard had a penchant for daydreaming to the detriment of his schoolwork and so did I. My teachers told my parents that I had constant flights of fancy and could not always differentiate between what is real and what is not. It appears I find myself in good company.

In Haggard’s case, however, his own father, who was a lawyer, considered him an imbecile not fit for the same expensive schooling as his brothers—Haggard even failed his army entrance exam and gave up on completing his diplomatic exams because he was too distracted by the goings-on of the occult society circles and spiritualists.

So his parents, out of desperation, sent him to South Africa to work unpaid for the lieutenant-governor of Natal (my birthplace). Going to South Africa was the best thing that could have happened to Haggard. It transformed him and changed his outlook on life. He embraced the frontier life and all it entailed. Haggard accompanied Sir Theophilus Shepstone into the Transvaal where Zulus, Boers, and the British fought for control of the land.

Technically speaking, in the Transvaal the conflict existed between the English and Boere only. The British were after the gold, see. The Boere had moved away from the Cape colony and trekked in-country and travelled to the Vrystaat and Transvaal to get out from under the British thumb who had taken over the colony. For a while there it looked like the British would leave them to their own devices, but then the Boere discovered gold. As for the Zulus, Natal was their natural territory and there is a long and bloody history between the Voortrekkers (Settlers –those who would become Boere) and the Zulus and between the British and the Zulus. In any event, Haggard became Registrar of the High Court in the Transvaal in 1878 at the age of 21. It is said that this period of his life provided the initial inspiration for his future novels.

After a failed attempt at farming in South Africa, due to safety concerns, Haggard and his wife later returned to England in 1882 and Haggard reluctantly picked up his law books again. He was called to the bar in 1884. Writing remained Haggard’s first calling, though, a calling he felt passionate about. His heart was never really in the law and he considered it a means to an end. Haggard wrote a non-fiction book on his own dime about Zululand in 1882. He also self-published his first novel, Dawn. It consisted of three volumes and failed to capture anyone’s imagination or attention in any meaningful way. His next attempt, The Witch’s Head, did better but the publisher limited the run to 500 copies.

And then he wrote King Solomon’s Mines—all because of a wager with his brother John who bet Haggard that he could not write a book as good or as popular as Robert Louis Stevenson’s novel Treasure Island.

Stevenson’s book broke from the mould. It wasn’t the usual expansive three-volume novel that was only available through circulating libraries. He published a thin one-off volume, cheaply priced, and sold it directly to the public. It created a whole new financial model that was considered revolutionary at the time. And because Treasure Island sold in the tens of thousand copies it created a new market, ripe for Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines.

Haggard wrote King Solomon’s Mines in six weeks and presented to the public a world exotic and strange. It’s a tale told in a simple and unpretentious way, featuring honourable heroes who follow a plain code of manly virtue while embroiled in a fantastic adventure. King Solomon’s Mines captivated the minds of millions of readers and was received with great critical acclaim. It sold over 30,000 copies in the first 12 months alone and was that year’s bestselling novel. I gather it was also the first-ever “best-selling” book if you consider how books were sold and distributed prior to Treasure Island. Funny enough, instead of selling the copyright to the novel for a £100, Haggard accepted a 10 per cent royalty, which, as it turned out, was one of his better decisions.

Allan Quatermain would appear in 17 more novels, starting with the sequel, Allan Quatermain, published in 1887. The swashbuckling adventure romances, She: A History of Adventure and its sequel Ayesha, followed. She alone would sell over 83 million copies by 1965.

In She, published in 1886, two adventurers search for the supernatural white queen, Ayesha, also known by a local tribe as “She-Who-Must-Be-Obeyed”, ruler of a lost African city called Kôr. Ayesha possesses supernatural powers and has been waiting 2000 years for the reincarnation of her lover.

She has been adapted to the cinema at least ten times and was one of the earliest films made in 1899, titled La Colonne de feu (The Pillar of Fire), by Georges Méliès.

She’s success was due to the story’s intoxicating exoticism. A story mixed with immortal desire and supernaturalism that was both new and strange and brilliantly captivating.

The sequel, Ayesha, was published in 1905 and is set decades after the original novel. Ayesha became a household name to whom Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung would both refer in their published works. Haggard is also remembered for Nada the Lily (a tale of adventure among the Zulus) and the epic Viking romance, Eric Brighteyes (1891) and The Wanderer’s Necklace (1914).

Financially secure and settled back at Ditchingham in Norfolk with his family, Haggard was able to travel extensively and so he visited the locations in preparation for the stories he wanted to write. For instance, Haggard visited the saga-sites in Iceland in preparation of his own saga stories, which gave Eric Brighteyes and The Wanderer’s Necklace the type of authenticity only possible through having traversed the frozen planes of Thule and breathing in its frigid air. Haggard dedicated Eric Brighteyes to “Victoria, Empress Frederick of Germany.”

Eric Brighteyes takes place in 10th-century Iceland and chronicles the titular character’s attempt at winning the hand of his beloved, Gudruda, the Fair. Her father Asmund, a priest of the old Norse gods, of course, opposes the match because he believes Eric is not good enough for his daughter. Then there is Swanhild, Gudruda’s half-sister and a sorceress, who desires Eric for herself, and so she introduces machinations to win him over, even if the cost is paid in blood. The book is filled with bloody battles and adventure, all soaked in a good helping of treachery.

Similarly, in The Wanderer’s Necklace, an eighth-century Norseman named Olaf Red-Sword, flees his homeland in Jutland after challenging the pagan ritual of human sacrifice. He travels to Constantinople to serve as a member of the Varangian Guard, sworn to protect Empress Irene Augusta from her son Constantine the Fifth. The tale takes the reader from Jutland to Byzantinum, to the pyramid tombs of Upper Egypt, and chronicles Olaf’s adventures in the Eastern Roman Empire. There is remarkable depth in this story with well-developed characters and complicated intrigue driven by conflict and love and raw, focussed emotion.

Haggard wrote many more books and truly became an author of world renown, able to publish two romances a year at a steady pace, and they kept selling very well, quickly making Haggard a rich man. In public, Haggard claimed only to write for the money as his “real job” was writing and advising the government about agriculture and the British colonies. But this was not true. That he wrote two books a year and named his three daughters after heroines in his stories only confirm that his creativity and “flights of fancy” could not be contained and required passionate release through writing, and that was the true fuel that drove Rider Haggard.

Haggard wrote these short books at break-neck speed and made very little editorial revisions. He once argued that revision would “stifle their primal energies”. Andrew Lang, the literary critic and friend responsible for getting King Solomon’s Mines into print wrote to Haggard thusly:

The more impossible it is, the better you do it, till it seems like a story from the literature of another planet.

Haggard would write three novels in collaboration with Lang who shared his interest in the spiritual realm and paranormal phenomena. Lang, a Scottish poet, novelist, and contributor to the field of anthropology, is best known as a collector of folk and fairy tales.

Haggard’s novels portray many of the stereotypes associated with colonialism, yet what made them unusual was the degree of sympathy with which he portrayed the native populations.

Africans often play heroic roles in the novels alongside the European protagonists. Two such examples are the heroic Zulu warrior Umslopogaas, in Allan Quatermain and Umbopa (Ignosi), the rightful king of Kukuanaland, in King Solomon’s Mines.

With fame came also those who would attack Haggard viciously for daring to break the mould by selling direct to the public and doing it so successfully.

The pretentious literati abused Haggard with vile accusations, calling his stories “sensationally plotted nonsense full of terrible schoolboy errors.” They would accuse Haggard of allowing the mortal sin of mixing romance and realism and riled at him for presenting “extreme violence in a jarring jocular tone,” and condemn his prose as “a symptom of the new cruelty and cynicism of mass culture.”

The Church Quarterly Review declared Haggard the “leading offender in the culture of horrible” and the Fortnightly Review accused his books of “wallowing in human abattoir, the romance only interesting as a measure of deplorable taste of the masses for cheap intoxication, like the swill sold in gin-houses to hopeless alcoholics.”

They did not pull their punches.

These hoity-toity clowns considered Haggard a cretin, saying the only possible pleasure one can gain from reading Haggard’s stories is limited to obtaining some insight into the conservative imperial mindset. Anything else was like regressing to a lesser state, both politically and aesthetically.

Author Henry James wrote an essay titled “The Art of Fiction” in 1884, after publishing A portrait of a Lady, in which he called the novel the highest aesthetic form. This ignited a debate and prompted Haggard to respond by writing “Why do men hardly ever read a novel?” Unfortunately, or maybe, fortunately, Haggard realised that he would forever remain on the outside of those that consider themselves arbiters of proper literature.

The insults continued in various degrees of discourteousness, thinly veiled as literary criticism, of course, and Haggard, attempting to possibly provide context and sway the tsunami of insults, wrote an essay in 1891, criticising the state of the modern novel in France, USA, and England. It failed its intended purpose and only widened the chasm between Haggard and his detractors. As a result, the attacks by the literary establishment became routine, and Haggard’s books were consigned to a minor place in children’s literature or the “embarrassing genre” of the imperial romance.

When insults failed to stop Haggard’s popularity, accusations of plagiarism followed. It hurt Haggard deeply for he considered himself a man of honour. The accusations added to the already dark melancholy clouds hanging low over him and it became such a heavy burden, Haggard almost gave up writing.

In a letter to a fan two years before his death, Haggard admitted that he knew he was looked down upon as a literary amateur, saying “born of a combination of country squire and public servant, and, to some extent, this is true. I have never set out to write modern novels.”

And yet, Haggard’s work received favourable regard from psychologists of the time. Carl Jung, famous Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst who founded analytical psychology, for instance, argued that “…such a tale is constructed against the background of unspoken psychological assumptions, and the more the author is unconscious of them, the more this background reveals itself in unalloyed purity.” Jung was, of course, referring to Haggard’s chosen form of storytelling and his feverish revision-free writing tempo.

C.S Lewis came to the same conclusion in his essay, “The Mythopoeic Gift of Rider Haggard”, saying: “What keeps us reading in spite of all the defects is of course the story itself, the myth. Haggard is the text-book case of the mythopoeic gift pure and simple.”

Roger Luckhurst, in his introduction to King Solomon’s Mines, Oxford University Press (Second Edition, 2016), said:

Like his contemporaries Robert Stevenson, Rudyard Kipling, and Arthur Conan Doyle, Haggard wrote at speeds as if to disconnect his conscious filters and allow the subliminal or unconscious mind to speak unedited. This stratum—a strange and wholly new conception of mind—was often figured as childish and elemental, the survival of an earlier evolutionary stage, savage and primitive. It was felt to have immense primordial power.

The Austrian neurologist and founder of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud, also came to Haggard’s defence–if one can call it that–and dismissed the idea that Haggard’s romances were simplistic. Instead, he argued that they can be seen as “complex and riven products of the depths of the mind of the sort his contemporaries in psychology were beginning to trace in all kinds of cultural expression.”

Freud found the very architecture of his mental life was built from elements of his compulsive reading of Haggard. Freud considered his vast tome on dreams as a Haggardian quest narrative, a perilous journey across unknown territory. Suffice to say, Freud was a bit of a fan of Haggard, despite literary snobs tearing it to shreds.

The one thing those who hated Haggard’s popularity could not change is that his stories remained popular and even today are still widely read. Ayesha, the female protagonist of She, has been cited as a prototype by both Sigmund Freud (in his The Interpretation of Dreams) and Carl Jung.

The English novelist, Graham Greene, in an essay about Haggard, stated, “Enchantment is just what this writer exercised; he fixed pictures in our minds that thirty years have been unable to wear away.“

Haggard was praised in 1965 by Roger Lancelyn Green, a member of the Oxford Inklings, as a writer of a consistently high level of “literary skill and sheer imaginative power.”

Haggard was made a Knight Bachelor in 1912 and later, in 1919, a Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire. Sadly, neither knighthood related to his fiction writing but for his work serving on several government commissions concerning agriculture.

Haggard passed away on 14 May 1925.

Despite the literati’s best efforts, Haggard’s stories remained popular and fuelled many a young boy’s imagination. His books influenced and inspired future great authors and set the foundation for a new genre that kept readers’ and writers’ imaginations occupied for over a century. And that is the real magic of storytelling. It’s not to impress or tick boxes to show levels of acceptability. Storytelling is supposed to draw a reader in and capture their imagination and keep them submerged until the end. Rider Haggard did that many times over, and literary critics will never take that away from him.

Sources:

Time Is Not an Arrow: Anima and History in H. Rider Haggard’s She

Freud’s fascination with H. Rider Haggard

Hidden Meaning: Andrew Lang, H. Rider Haggard, Sigmund Freud, and Interpretation

List of works by H. Rider Haggard

She: A History of Adventure (Wikipedia)

The Literature Network: Biography of H. Rider Haggard

Encyclopaedia Britannica: Sir Henry Rider Haggard

Fantastic Fiction: H. Rider Haggard

An excellent, well-researched post, Woelf! The one great advantage of coming to HRH late–as I did–is that there are about 70 Haggard novels to look forward to.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for the kind words. I ended up writing a far longer post than I originally intended but I felt the information was important. Also, I would lie if I said I didn’t enjoy it.

The other good thing, as you say, is that my to-read pile just jumped exponentially in size.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oops! I miswrote/misremembered. HRH “only” wrote nearly 60 novels.

BTW, I hyperlinked this post in my new HRH blog entry:

https://dmrbooks.com/test-blog/2020/5/15/h-rider-haggard-95-years-gone

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cool!

LikeLike

I thoroughly enjoyed this. I could not put King Solomon’s Mines down once I started reading. (Believe it or not, I found a leather-bound edition in a Goodwill store for $3.00!)

And this: “It appears I find myself in good company.”

Loved that line. I can identify.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wholly understand how Haggard inspired other writers, and, admittedly, given how I had issues with reading too many books instead of focusing on school work, it was nice to learn about another having the same affliction. Thanks for commenting.

LikeLike

Thank you for a great article about one of the founding fathers of Adventure fiction. HRH is indeed a gift and, as you point out, too many people have forgotten or never knew his name to begin with.

I recommend any one of the books you have mentioned here to any reader who has a taste for adventure. You won’t be disappointed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Indeed! Thank you for the kind words.

LikeLike